As the COVID-19 virus creeps along the globe, taking lives, crippling economies, and even bringing entire countries to their knees, its easy to feel like we as individuals are helpless against its onslaught or too powerless to make a difference in its outcome. It’s easy to lose faith in humanity when we read about price-gougers and plague partying while others are struggling to stay alive or suffering under extreme quarantine conditions. It’s not only good and necessary to take Fred Rogers’ oft-quoted advice at times of trouble to “Look for the helpers;” it’s also a powerful form of self-care and an affirmation of the worth of individuals.

We started the “Legendary” category on this site for two reasons, both of which are bound up in each other. The first reason was to promote our book, obviously. But the second reason was to finally have a category in which all of our musings on questions or matters of LGBTQ life or history could come under one banner. Sometimes, we use it to flesh out some of the stories and legends in the book; serving almost as a sort of addendum (such as our profiles of Crystal LaBeija, Storme DeLarverie, Hibiscus and the Compton’s Cafeteria riots), or a syllabus (such as in our Essential Viewing posts). Other times, we just use it to talk about matters of queer history, both past and present. Current events give us a chance to do all three here.

See, in Chapter 9 of the book, we use the Untucked scenes of family and friends sending messages of support to the queens as a jumping off point to discuss the history of queer people and their families; whether that’s the family of their origins and how they navigated the nearly impossible question of their queerness with them, or the family that they made for themselves out of other queer folks and allies. Ru has said it many times during the show, ” As gay people, we get to choose our own families.” Of course, that’s true of everyone, but Ru’s point is that queer folks have traditionally had to rely on a more communal definition of family because until fairly recently, almost all out queer people were rejected by their families and no queer people could legally marry or adopt children. The traditional roads to family were quite literally closed off to queer people, on both a personal and societal level. And no period during the last century of queer life demonstrated that point so devastatingly than the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, which utterly ravaged the gay community, killing off an entire generation of queer folks while society – and even their very families – stood by impassively, ignoring them utterly.

It was in this environment that people from both inside and outside the queer community came together to provide solace, comfort, necessities and dignity to a generation of queer people ravaged by AIDS. Drag queens twirled and joked and lip-synced to raise money for research or to provide assistance to people living with HIV/AIDS. Gay men and women organized politically and took to the streets to scream their rage and shame the community at large in organizations like ACT UP. Men and women of all backgrounds provided assistance, helped organize meds and doctor’s appointments, drove the sick to where they needed to go and made sure they had enough to eat and, when it was time, made the arrangements for their burials, because there was no one else to do it. It was a time of great fear, loss, and despair but it was also a time where queer people and their allies came together and did every single thing in their limited powers to provide help or to end the pandemic as quickly as possible. We highlighted many of these groups and people in Chapter 9 and some of their stories are so poignant, so devastating, that when it came time to read them aloud for the audiobook, we broke down repeatedly. But for the purposes of today, let’s just highlight one group of women mentioned in the book, whose selflessness in the face of tragedy became an inspiration to an entire community: The Blood Sisters of San Diego.

In 1983, as AIDS hysteria began ascending to a fever pitch, gay men were prohibited from donating blood (a restriction that still exists to this day). This was at a time not only when the dying often needed blood transfusions, but when the medical community reacted to queer people with AIDS with disgust, shunning, and even ridicule. It was a time when the people dying of AIDS felt they had no one to turn to for help. And it was in this atmosphere that a woman named Barbara Vick gathered together her lesbian sisters in the San Diego Democrats for Equality organization, and asked them to come together to form a blood drive for the dying men who were their gay brothers. Understand that, post-Stonewall, there occurred something of a split between gay men and lesbians both politically and socially, as many queer women of the time felt far more kinship with the growing feminist movement than the cis male-centered gay rights movement. Vick was posed the not-unfair question many a time: “Why do this when we know they wouldn’t do this for us?” And the answer was always the same: “Do it anyway.”

Barbara organized the first Blood Sisters blood drive in July 1983, hoping she could get 50 women to show up. Two hundred women came that day to offer their support, their allyship, and their very blood to vulnerable people who had nowhere to turn. The Blood Sisters of San Diego, like so many of the women who did the back-breaking work of tending to a plague-ravaged family, became legends and stand as a testament to what people can do in a time of pandemic, when there seems to be nothing left in the world but fear and mistrust. We can weather this. Why? Because people weathered far worse in recent memory and not only survived, but showed the world a new definition of family.

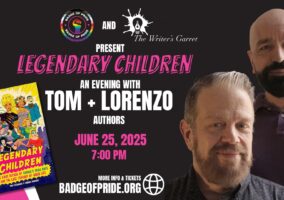

“Our book Legendary Children: The First Decade of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Last Century of Queer Life is on sale now!

The Los Angeles Times called it “a nuanced exploration of the gender-bending figures, insider lingo and significant milestones in queer history to which the show owes its existence.” The Washington Post said it “arrives at just the right time … because the world needs authenticity in its stories. Fitzgerald and Marquez deliver that, giving readers an insight into the important but overlooked people who made our current moment possible.” Paper Magazine said to “think of it as the queer education you didn’t get in public school” and The Associated Press said it was “delightful and important” and “a history well told, one that is approachable and enjoyable for all.”

Yea or Nay: Fendi Promenade Loafers Next Post:

“Legendary Children” Press and Review Updates

Please review our Community Guidelines before posting a comment. Thank you!