Pin

Pin

“Now I wouldn’t presume to tell a woman what a woman oughtta think, but if a woman’s gotta think, think pink!”

Kay Thompson sung those words in 1957’s Funny Face, playing a Diana Vreeland-esque editor of a Vogue-esque fashion magazine. The song wasn’t the point of the film, which was largely about Audrey Hepburn reluctantly becoming a supermodel thanks to the loving lens of photographer Fred Astaire, nor is pink one of the film’s more prevalent colors in art direction or costume design. It was an interlude to describe the film’s high-fashion world setting and the thinking of the people who drive it. Thompson, as Maggie Prescott, sang of a world devoted entirely to the wearing and celebration of pink. It was a world of surface beauty and frivolous interests – and it was a world dominated by women, of course.

Pin

Pin

Sound familiar?

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie has finally seen its release (our review is here) and has became a true Cultural Moment at a speed that seems dizzying, but only if you haven’t been paying attention. Barbie‘s pink, patriarchy-rejecting world (and its accompanying real-world style trend Barbiecore) might seem like it sprung up out of nowhere, but we would argue that Gerwig’s vision of female supremacy has its roots in the long history of cinema and specifically references a particularly 21st century politicized view of what the color represents.

Because film is such a visual medium, it tends to trade in a lot of encoded semiotics and symbolism, often perpetuating themes, motifs, and cultural norms through decades and generations. Mainstream films especially have a need to simplify their symbols and to stick to relatively middle-of-the-road (read: socially conservative) sensibilities. Despite decades of accusations by conservative and right-wing provocateurs, pundits, and politicians, “Hollyweird” is not and never really has been the vanguard for progressive social change. Film and television are products; usually very costly ones that require mass appeal and huge audiences in order to recoup the costs of them. This is all a slightly wordy way of saying that the history of movies is positively rife with pink-is-for-girls costume coding, with occasional side trips into “pink is for gays” territory.

Pinks in Cinema

Ranging in hues from the bubblegum-colored gown worn by Lorelei Lee (Marilyn Monroe) during the “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” number in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, to the pastel pink of Carrie White’s (Sissy Spacek) “dirty pillows”-baring prom gown in Carrie, to the saturated fuchsia of Jessica Rabbit in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (“I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way,”) to the soft salmon of Dr. Ellie Sattler’s (Laura Dern) button-down oxford shirt in Jurassic Park or the peachy-pink of Dottie Hinson’s (Geena Davis) Rockford Peaches uniform in A League of Their Own, pink costumes on female characters in major motion pictures all too often signal a woman defying men through her actions, flipping the bird to chauvinistic prejudices or expectations and rendering everyone around them (but mostly the men) helpless in the face of her overwhelming sexual power. That is, when they’re not wielding their femininity against other women, of course; such as the Pink Ladies of Rydell High in 1978’s Grease (“It’s senior year and we rule the school!”). In Pretty in Pink (1986), the color is used to denote romance and femininity, but when Andie Walsh (Molly Ringwald) literally deconstructs a vintage pink dress and remakes it into an ’80s-appropriate one in order to go to the prom without a date, she says, “I just want them to know that they didn’t break me.” In 20th Century mainstream cinema, pink signified female frivolity, female sexuality, female defiance and female liberation – sometimes all at the same time.

At the turn of this century, however, the connotations took a more openly and distinctly anti-patriarchal turn, as if to say that women – and by extension, queer people or men who didn’t act appropriately masculine – were foundational threats to cis male hegemony simply by existing. It morphed from a color with undertones of love, sex and femininity to something that signals a threat to the patriarchal order, a threat to cisgender heterosexual male hegemony, and a threat to “good girls” who tend to be helpless against their manipulations.

The Trailblazer: Elle Woods, played by Reese Witherspoon in Legally Blonde (2001)

The Costume: A pink long-sleeved dress with satin cuffs, a satin lapel collar, a rhinestone beaded satin sash, rhinestone cufflinks, pink rhinestone beaded sandals, a pink rhinestone beaded Hermes bag, designed by Sophie de Rakoff.

The Quote: “What? Like it’s hard?”

![]() Pin

Pin

The character of Elle Woods not only subverts the pink-is-frivolous trope, but it’s also the entire point of her character. When Elle is introduced to the audience, she is aggressively pink’d out, with the usual sorts of style motifs used to associate pinkness with frivolous femininity: sparkly, fuzziness (faux fur phone), naïve romanticism (her heart-shaped notepad). As she attempts to fit into the culture and live up to the expectations of Harvard Law School, her wardrobe shifts to more “serious” colors like blue, green and even black. At the climax of the film, upon realizing that she can succeed by being true to herself, she triumphs in the courtroom wearing a bright pink dress with a satin pink collar paired with pink sparkly sandals. She achieves greatness and fullness of purpose and slays her own dragons while embracing the “girly” parts of herself. She is continuously dismissed and underestimated throughout the film, not because she lacks intelligence, but because she fails to embody the code of intelligent, serious womanhood, represented by her twinset-loving rival or the black suited lawyers (male and female) who buffet her from all sides. Her love of pink and frills and sparkle are supposed to denote a lack of seriousness or ambition but in the end they were an illustration of how easily Elle outshone her competitors, to the point where she could devote considerable time and energy to matching her shoes to her bag to her dog’s collar to her pen and still outpace all her supposedly more serious peers.

What’s So Special About Pink?

In terms of critical analysis, whether you’re talking about literary, film or art criticism, applying symbolic meanings to specific colors is often a dicey proposition. Anyone who chooses to engage in that sort of analysis should be upfront about how personal and idiosyncratic the conclusions drawn from it are likely to be. Sure, you can state with some confidence that red, for instance, denotes passion or anger or violence, largely due to its associations with blood or fever. But depending on the culture or the context, you could also note that red denotes luck or death. Green is often used as a symbolic synonym for envy, but it can also denote money or nature or even illness or poison. Blue can evoke wide open skies or it can refer to the Madonna of Renaissance paintings just as easily as it can be encoded to signify a baby boy. White can be seen as a color denoting purity or virginity, but it could just as easily be an encoded racist reference announcing white supremacy. And in many cases in literature or art, one color can encompass every one of its denotations at the same time. Pink is different, though. Pink has had fairly consistent connotations of and connections with frivolousness and femininity for close to a century now, although it wasn’t always seen that way.

In the 19th Century and the first half of the 20th, pink was a common color in which to dress baby and toddler (but never older) boys. Nineteenth and early twentieth century portraiture of baby boys and toddler boys in dresses of pink are evidence of a certain sort of practicality (training a pre-school aged boy on how to pee and poop in a civilized manner is a lot easier if you don’t have to worry about pants) just as much as they tend to imply the idea that a boy in a pre-age of reason stage in their life may as well be a girl, existing in a sort of “pre-male” state of wildness and lack of discipline. When young boys graduated to wearing pants, they immediately stopped wearing pink.

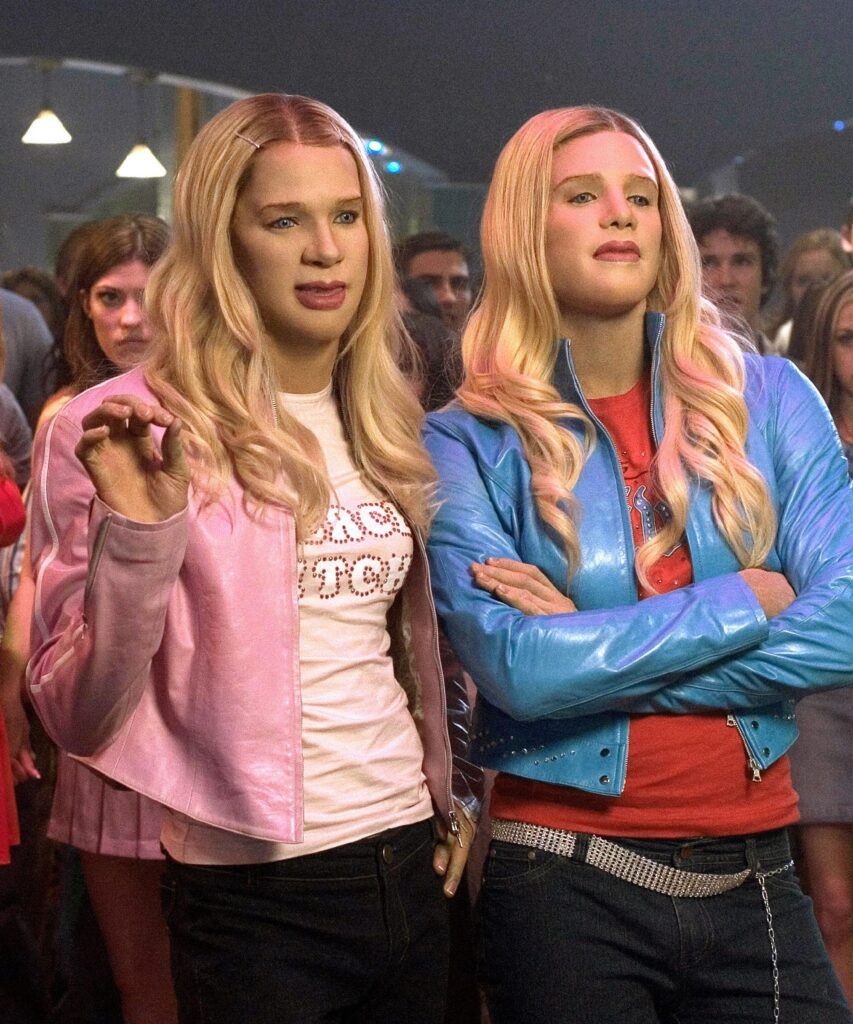

The Imposter: Marcus Copeland/”Tiffany Wilson,” played by Marlon Wayans in White Chicks (Dir. Keenan-Ivory Wayans, 2004)

The Costume: A pink leather jacket, pink baby tee with “FIERCE BITCH” spelled out in pink rhinestones, a large goth cross necklace made out of pink costume gemstones, a multi-colored Louis Vuitton bag, and dark-wash jeans, designed by Jori Woodman.

The Quote: “What’s up, money? You got a problem? What you looking at my ass for?”

Pin

Pin

In White Chicks, Marcus and Anthony Copeland (Marlon and Shawn Wayans), two brothers and FBI agents, wind up going undercover and posing as Brittany and Tiffany Wilson (Maitland Ward and Anne Dudek), two white socialites who have been marked for a kidnapping. The cult classic mined a lot of low comedy out of two Black men trying to pose as vapid young white women, which they pulled off (not really) through the use of blonde wigs, blue contact lenses, a ton of pancake makeup and white face powder, and … lots and lots of pink ensembles. The Wilson sisters were parodies of Paris and Nicky Hilton, two socialites and reality stars known at the time for their sparkly, girly, frivolous outfits. Like so many of the characters mentioned in this essay, the brothers wear more than one pink costume in the film; often baby tees with very aughts, very Paris Hilton-esque phrases on them, like “A-Dior-able” or “Dude, Where’s My Couture?”

Through a series of unlikely circumstances that could only happen in the broadest of comedies, Marcus, as Tiffany, is forced to go on a date with basketball pro Latrelle Spencer (Terry Crewes), who is utterly smitten with “her.” They go to a fancy restaurant, where “Tiffany” picks at her athlete’s foot, orders unladylike or indelicate foods like a steak smothered in onions, a rack of ribs, and pasta with garlic. She farts, laughs with food in her mouth, and opens her jeans after she’s had too much to eat, exposing her hairy stomach to her date, who is inexplicably charmed by this behavior – or more accurately such a horn dog that he’s willing to ignore it all. The audience is meant to see a juxtaposition between her feminine appearance and her masculine-coded lack of social graces because as we all know, pink is for ladies and those ladies are supposed to act a certain way that doesn’t involve farts or threats of violence.

Later, in a dance-off with the Wilson sisters’ nemeses, the Vandergeld sisters, the brothers take over the dance floor to Run DMC’s “Tricky,” spinning and breaking to everyone’s astonishment. Again, not to over-explain comedy, but the audience is meant to laugh at not only the unlikely spectacle of white girls clearing a dance floor to a rap song, but also at the decidedly unfemme and unsexy style of dancing they execute. There’s this constant comedic tension between their feminine attire and their masculine behavior, the white girls they’re emulating and their own existence as Black men; the feminine-coded mean girl aggression they’re constantly subjected to (and bad at countering) and their own masculine-coded aggressive tendency to throw fists or reach for their guns.

The History of Pink

For a good portion of its history as a textile and design color, pink was seen as a variant of red – which it is, of course, when you strip it of the gender coding assigned to it in the years since. But before it became associated with femininity or femme behavior, it had red-toned connotations of blood, passion, and even violence (these connotations never actually left but put a pin in that idea for now). In 1936, American fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli offered a major shift in how people thought about pink when she envisioned and created a perfume bottle in the shape of a woman’s body, inspired by the measurements of one of cinema’s earliest blonde sex goddesses, Mae West. She called the perfume “Shocking” and packaged it in a brilliant, vibrant shade of pink dubbed “Shocking pink,” which became a signature of her aesthetic. Here we see the establishment of pink as a reference to female sexuality and it’s no coincidence that it utilized the iconic image of a female movie star in order to make that connection.

At the midpoint of the Twentieth Century, pink became seen as a female color almost exclusively, helped in large part by two iconic aspects of the Baby Boom: the election of World War II general and national hero Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, whose presidency would come to define the 1950s, and the rise in popularity of baby showers that came with the post-War baby boom and the mass adoption of a middle class suburban lifestyle for most white Americans. First Lady Mamie Eisenhower was such a fan of the color – she wore it to the inauguration and decorated the White House with so much of it that the press called it the Pink Palace – that a particular shade of it named after her – Mamie Pink – became one of the most popular colors of the 1950s, used in everything from women’s fashion to appliances and household products, which were marketed and sold to women, of course.

With the Baby Boom came a need for a lot of baby paraphernalia among a huge swath of the post-War population and it soon became commonplace for middle-class women to gather for the purposes of giving or securing needed items for infant care. Because they’re social events centered entirely around a pregnant guest of honor in order to literally celebrate and support their pregnancy, themes and party games based on guessing the gender of the baby-to-come evolved to be the order of the day and what had already been an allusion got turned into a strict code: pink is for girls, blue is for boys.

The All-American Girl: Megan Bloomfield, played by Natasha Lyonne in But I’m a Cheerleader (Dir. Jamie Babbit, 2000)

The Costume: A schoolgirl uniform consisting of a light pink short-sleeved blouse and a vivid pink skirt paired with white anklet socks and Mary Janes, a gold cross necklace, designed by Alix Friedberg

The Quote: “Oh my God, I’m a homosexual!”

Pin

Pin

When high school cheerleader Megan Bloomfield is sent away by her parents to a conversion therapy camp called New Directions, camp director Mary Brown (Cathy Moriarty) greets her in a vivid pink suit before taking her up to her dorm, which is rendered entirely in shades of pink. She is told she cannot wear anything but the hospital gown provided for her until she admits the truth of herself. When she’s berated by the other camp attendees during group therapy, she comes to the realization that she’s attracted to girls and promptly receives an all-pink uniform in order to begin the process of curing her homosexuality and embracing appropriately feminine comportment. This is, of course, all presented tongue-in-cheek in a comedic film and Megan is already about as femme as any teen girl can be, but the kind of people who are most threatened by gayness tend also to be the kind of people who are most desperate to keep all the traditional signifiers locked into place. At New Directions, all the women and girls wear pink only and all the men and boys wear blue only. Despite the rigid enforcement of these codes, the entirely femme-presenting and exclusively pink-wearing Megan does not embrace the heterosexuality others keep trying to impose on her.

The Implied Violence of Pink

One could argue a sort of horrifying symmetry closing out the Baby Boom years when another First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, made her own iconic contribution to the semiotics of pink. Her pink boucle tweed Chanel-inspired suit was splattered with the blood and brain matter of her husband, President John F. Kennedy when he was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. A former photojournalist with a keener sense of political symbolism than most gave her credit for at the time, Jackie refused to remove the gore-splattered suit on the plane ride back to Washington, wearing it to Vice-President Lyndon Johnson’s hasty swearing-in and disembarking in full view of television cameras, literally caked with her husband’s blood. “I want them to see what they’ve done,” she is reported to have said when aides suggested she change out of it.

The Innocent: Patsey, played by Lupita Nyong’o in 12 Years a Slave (Dir. Steve McQueen, 2013)

The Costume: A ragged, worn, pink cotton Empire waist dress with puffy sleeves and a pink head scarf with a peony print, designed by Patricia Norris.

The Quote: “Five hundred pounds of cotton! Day in, day out! More than any man here! And for that, I will be clean!”

Pin

Pin

When we first encounter Patsey, she is sitting in the sun, humming to herself and making corn husk dolls. Her youth, girlishness, and innocence is underlined and spotlighted as she presents a picture significantly more serene than most of the imagery in the film.

Her pink dress and floral head scarf seem incongruously pretty and rich for a woman of her station and it stands out significantly in the film because almost all of the other enslaved characters are dressed in beiges and grays. Costume designer Patricia Norris discovered in her research that enslaved people were often given old clothes once worn by their enslavers. Empire waists were popular in the 1830s, roughly 25 years before the time of Patsey’s introduction; the implication being that she is wearing dresses once worn by her enslaver’s wife – and her own nemesis – Mrs. Epps (Sarah Paulson), who seethes with jealousy toward the young woman and subjects her to physical and emotional torments because of her husband’s lust for her. Because none of the other women who work the fields alongside her are ever shown to be dressed in anything this bright and pretty, it’s not hard to conclude that her enslaver and sexual abuser Mr. Epps (Michael Fassbender) gave her the prettiest of his wife’s castoffs. Through absolutely no fault of her own, merely by existing, Patsey is a major disruption to How Things Are Supposed To Be. She does not and cannot stand in defiance of the patriarchy like so many of the other examples here, but she does stand as a defiant example of how it treats those it considers less than. How a person’s very existence is seen as a threat. It’s not that she upsets the order – she has no power to do so – it’s that the order finds her upsetting. There’s a huge difference, the result of which is an unfathomable level of violence visited upon her.

But the connection between pink and violence isn’t limited to those who are victims. It can also be a color associated with the ones who enact that violence, like Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) in 1975’s Carrie, whose pale pink prom dress gets drenched with pig’s blood by a vindictive classmate (the connections between pink and female aggression in cinema are legion), causing her to snap and kill her entire class. There’s something about the softness and implied docility conventionally associated with pink that makes it perfect for the kind of cinematic visual twist provided by splattering it with blood, whether literally or figuratively.

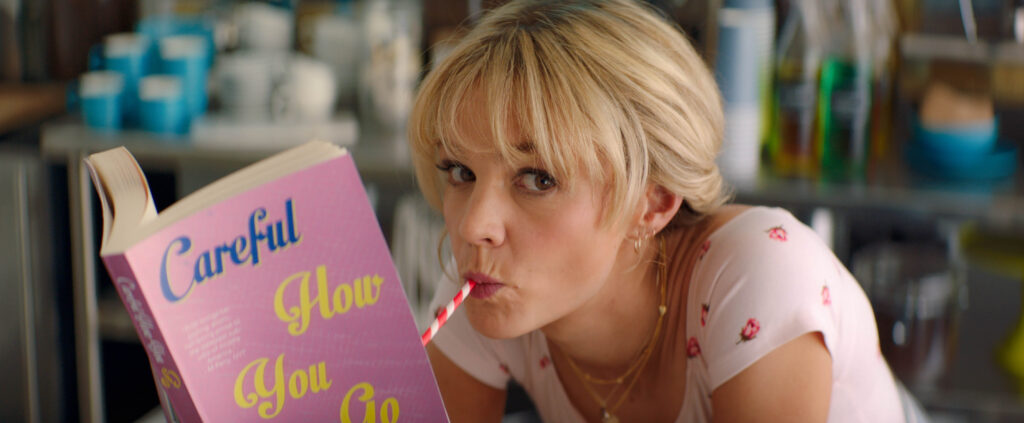

The Siren: Sandie, played by Anya Taylor-Joy in Last Night in Soho (Dir. Edgar Wright, 2021)

The Costume: A pink chiffon tent dress with pin tucks at the neck and silver diamante trim, silver slingbacks with a kitten heel, designed by Odile Dicks-Mireaux.

The Quote: “You’re better than this.” “I don’t think I am.”

Pin

Pin

It may not be iconic just yet, but the pink mini-dress worn by Sandie (Anya Taylor-Joy) as she made her way through the swinging 1960s London scene is a perfect representation of how pink and traditionally feminine styles can be used to create a character who’s not only more than she seems and far more dangerous than anyone realizes, but also turns her into a figure of desire and obsession to everyone who comes in contact with her. The floaty, almost daintily feminine style had a demure sexiness to it that was pretty much the hottest style of the mid-sixties, straddling that moment between the clean, glamorous mid-century sexiness of Marilyn Monroe and the looser, wilder post-hippy styles to come. It’s a youthful look that hearkens to some of the most glamorous actresses and female sex symbols of the Swinging Sixties period, like Brigitte Bardot, Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Fonda. This explains why Sandie is wearing it, why so many men fall at her feet, and why a fashion student in the present day might become obsessed with it.

The dress became something of a totem for Eloise (Thomasin McKenzie), the psychic fashion student in 2021 who keeps having visions of the would-be It Girl of half a century before. Eloise goes to sleep one night and dreams of being the beautiful and alluring Sandie at the famous Cafe de Paris in 1965. In an astonishing dance scene, Sandie morphs back and forth with Eloise as they both dance with Jack (Matt Smith), who will become Sandie’s boyfriend, manager and possible abuser. Taylor-Joy makes full use of the pink chiffon in this scene, pulling it out and over her head and then allowing it to billow around her as she twirls.

Eventually, Eloise starts losing contact with the real world and the people who care about her because she becomes obsessed with revisiting Sandie’s life and walking in her stylish shoes every night when she goes to sleep. She sketches the dress for her design class and spends several scenes working on a version of it, eventually producing an entire line of runway looks based off of it. The dress becomes a symbol for her own obsession with the past and the unhealthy hold it’s taking over her. When a film imbues that much meaning and symbolism to one costume, it’s a costume worth considering and interpreting.

Sandie is introduced as an alluring temptress, then she is cast as a victim of the men who exploit girls like her, until finally, she is revealed to be much more complicated (and darker) than anyone ever considered, largely because of her tendency to wear pretty, sexy, stylish fashion, which causes everyone to underestimate her. In the end, her siren call spelled doom for some of those men, until it echoed through the decades and became one girl’s obsession in the modern day; a pink dress full of secrets, splattered in blood.

Pink Aggression

But we can also look at pink in less extreme framing than its connection to violence. Think of Sandra Bullock in the poster for Miss Congeniality wearing a traditional pink pageant queen gown paired with a thigh holster and combat boots. It’s a costume that gets constantly referenced around Halloween and you can still buy versions of it from costume sites twenty years after the film. It’s telling that this image is the one people most remember from the film because Bullock never actually wore that dress in it. Part of the reason it’s such a memorable image is because it sums up a pervasive modern trope regarding pink and femininity; pink, when wielded by a proficient wearer, can be used as a weapon.

The Alpha: Regina George, played by Rachel McAdams in Mean Girls (Dir. Mark Waters, 2004)

The Costume: A pink cardigan over a white t-shirt that reads “A LITTLE BIT DRAMATIC,” a black tulip mini skirt, black thong sandals, a pink cherry blossom Louis Vuitton handbag, an R diamond pendant, designed by Mary Jane Fort.

The Quote: “Get in, loser. We’re going shopping.”

Pin

Pin

Like their cinematic grandmothers The Pink Ladies of Grease, the Plastics are the ruling female clique at North Shore High. Regina George is the reigning queen bee, enforcing rigid rules of comportment for her fellow plastics, Gretchen Wieners (Lacey Chabert) and Karen Smith (Amanda Seyfried). One of those rules – “On Wednesdays we wear pink” – is meant to separate the group from their contemporaries, ensuring that everyone knows who is a Plastic and who isn’t. It’s also, as the film demonstrates repeatedly, a rule that’s born entirely out of Regina’s own life and personal taste. As Cady (Lindsay Lohan) puts it once she’s allowed to become a member of the group, “Regina’s like the Barbie I never had.” But those on the outside of the in-crowd tend to see her in a slightly less benign light. “She’s fabulous, but she’s evil,” Cady’s friend Damian (Daniel Franzese) warns her. As Cady becomes more obsessed with Regina, she becomes more like her, which means her costumes become more and more pink as the film progresses. At one point, she wears the “A LITTLE BIT DRAMATIC” tank with a pink cardigan while sporting the same pink Louis Vuitton purse, in perfect cosplay homage to her tormentor/tormentee. Pink as weapon, but also pink as obsession.

With her iconic “A LITTLE BIT DRAMATIC” ensemble, which only has pink accents rather than being all one color, you can see how Regina keeps her pink to simple, expressive touches in her overall look, rather than succumbing slavishly to a rule or trend, unlike the other Plastics and very much unlike her “cool mom (Amy Poehler),” who greets the girls in a pink velour Juicy Couture track suit. Nevertheless, it remains an overwhelming constant in her life and her wardrobe; not just in her pink-decorated bedroom and her pink-wearing wannabe of a mother, but in her main weapon: the Burn Book’s hot pink cover.

This same idea is demonstrated in another aggressive, if not entirely powerful female character, who wears pink constantly in order to hide her rage, but doesn’t make it the entire point of her existence.

The Avenger: Cassandra, played by Carey Mulligan in Promising Young Woman (Dir. Emerald Fennell, 2020)

The Costume: A succession of sweetly twee pink tops and sweaters with floral motifs, culminating in a sexy nurse costume with a multi-colored wig with streaks of pink and a pair of pink rubber gloves, designed by Nancy Steiner.

The Quote: “Can you guess what every woman’s worst nightmare is?”

Pin

Pin

Like so many of the women in this essay, Cassandra – or Cassie – doesn’t just wear one pink costume in the film, she sports a succession of them, mostly in the scenes when she’s play-acting at being normal (and failing at it): on the job at a pastel-colored coffee shop and on dates with her would-be boyfriend. She adopts a harmless pose (right down to the infantilizing of her name), sports pigtails, and wears soft pink sweaters with floral motifs. When she lets her guard down and believes that she might be happy with nice guy Ryan, she’s seen in a vivid pink cardigan, pale pink jeans and a pink floral shirt. In this sense, she’s using pink to mask the anger she’s feeling. At the film’s climax, when she enacts a twisted form of revenge on her best friend’s rapist, she is dressed in a stripper-nurse costume, pastel-streaked wig and bright pink rubber gloves, as if she were still holding on to a little bit of that mask, even as she spiraled toward her combination of vengeance and doom.

The Threat of Unwelcome Femininity

But pink also had allusions to what was perceived as an unwelcome femininity decades before the rise of the post-War baby boom and those allusions could take a very dark turn. Men accused of being gay or gender non-conforming in Nazi Germany were sent to concentration camps and eventually forced to wear pink triangles on their prisoner uniforms to identify their offense for all to see. Pink, a color now laden with queer and feminine undertones, was turned into a weapon to use against the very people it symbolized in order to shame those who didn’t uphold patriarchal norms.

At the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, gay advocacy groups reclaimed the pink triangle as a symbol of hope, defiance, anger and community, with its most famous and iconic usage being the “Silence = Death” campaign, which was started by a small queer art collective in New York and then appropriated by the powerful and noisy AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP); a group with a history of staging die-ins at cathedrals or spilling blood down the steps of the Stock Exchange in order to call attention to exorbitant AIDS treatments. This was more of a fuck-you form of pink, which would later be lightly echoed in the pink pussy hats of the 2017 Women’s March.

The Brawler: Margot Robbie as Tonya Harding in I, Tonya (Dir. Craig Gillespie, 2017)

The Costume: A pink sequined skating costume with shredded sleeves, a tulle skirt and a sequined bow, designed by Jennifer Johnson

The Quote: “Suck my dick!”

Pin

Pin

Despite wowing crowds with unconventional skate routines set to Z.Z. Top songs, world class figure skater Tonya Harding routinely fails to score as high as her more conventionally feminine peers. After arguing with her coach and announcing that she won’t dress like the tooth fairy in order to please the backwards-thinking judges, the rough and uncultured Tonya is eventually seen making a new skate costume that practically explodes with cartoonish child pageant femininity. It is entirely pink, of course. This is after a clearly established preference for more ‘80s-trendy, rock-and-roll inspired costumes of purple and silver or black and gold. Still, she’s nervous about ensuring that it meets the standards of the conservative judges she’s constantly battling. “Does it need more tulle?” she asks her boyfriend Jeff (Sebastian Stan). “Tulle’s classy, you know?” Despite practically radiating a Barbie doll pink form of frantic femininity, her sparkly costume does not allow her to score any higher in her next competition. Filled with rage and lacking an ability to effectively process it after a lifetime of physical and emotional abuse from her mother, she tears into the judges for punishing her lack of comportment (“You know,” one judge sneers, “We also judge on presentation”) and the fact that she can’t afford the kind of expensive costumes the other girls are wearing. She begrudgingly tried to meet the establishment on their restrictive terms (“I dressed pretty!” she yells to her coach later), but she found their version of femininity suffocating and in the end, immaterial to her skills. She couldn’t articulate it without offending everyone, but she wasn’t wrong and the film makes it more than clear that her life would have worked out differently had the skating establishment been less punishingly conformative, a life course she happens to share with the former Queen of France. No, really.

The Punk: Marie Antoinette, played by Kirsten Dunst in Marie Antoinette (Dir. Sophia Coppola, 2005).

The Costume: A pale pink gown with a squared off, low-cut neckline surrounded by ruffles, a pink satin skirt with panniers, topped off by a pink wig and pink flower crown, designed by Milena Canonero

The Quote: “Let them eat cake.”

Pin

Pin

Marie Antoinette opens with a shot of the title character surrounded by a dozen pink cakes and lying on a chaise in a white undergown with pink crinolines as a maid tends to the pink satin shoes on her feet. Director Sophia Coppola studded the film’s soundtrack with punk classics in order to underline Marie as a symbol of don’t-give-a-fuck excess in the punk mode, with candy switched out for drugs and jewels switched out for safety pins.

Marie’s love of fashion and fine things is positioned as a potentially nation-destroying practice and Sophia Coppola chose pink, with all of its feminine-coded markers – satins and flowers and candies and shoes and feathers and hats – to render it to the audience. This foreign upstart, this youthful influencer, all in pink while sitting on couches of pink in rooms full of pinks eating pink foods, was seen as the ruin of France. Director Coppola re-envisioned the former Austrian princess as a punk rebel not by changing her into something edgier, but by changing the definition of what’s edgy. Similar to other pink teen queens like Regina George in Mean Girls or the Pink Ladies in Grease, Marie doesn’t stand out as a sole figure in pink; she becomes the trend-setter whose tastes wind up changing the court around her as pink explodes all over the film and in the costumes of the women and some of the men surrounding her.

It would be difficult to choose just one of the literally dozens of pink costumes worn in the film as the best example of this motif, but when she was formally introduced to Count Fersen (Jamie Dornan), who she would soon after take as a lover, she was about as pink as it was possible for her to be, in a pale pink satin gown and a pink wig festooned with pink flowers. Throughout the film, Marie is seen by members of the court – and later, by all of France – as a distinctly dangerous figure threatening the order of things. Her love of the frivolous is rendered visually not just in the cakes and candies and macarons that stud practically every scene of the film (to the sounds of ‘80s classic “I Want Candy), but in her excessive, almost pathological love of pink. Like Tonya Harding’s explosion of sequins and tulle, the doomed Queen of France’s aggressively pink aesthetic and the lifestyle it represented was considered the wrong form of femininity by the people in charge of her fate.

Pink Against the Patriarchy

Anytime you assign a neutral concept like color a female-specific meaning or use it as a slur against men perceived as unmasculine, you’re placing that color in the column labeled “Not The Patriarchy.” While gender-coded colors aren’t quite so rigidly adhered to today as they once were, pink still tends to denote womanhood and sometimes homosexuality when it’s deliberately utilized as a symbolic color, which is why it can be deeply upsetting to see someone who is neither of those things wield it so effectively.

The Rebel: Elvis Presley, played by Austin Butler in Elvis (Dir. Baz Luhrmann, 2022)

The Costume: A pink, oversized rockabilly suit consisting of baggy pants, a drape jacket with bi-color lapels and a black yoke across the back, black-and-white saddle shoes and a black lace shirt.

The Quote: “Come on back to me, little girl/So we can play some house”

Pin

Pin

Even a straight, white, God-fearing Christian man can wind up being a threat to the patriarchal order, so long as he’s horny enough, hot enough, and good enough at appropriating the work and styles of Black artists to launch his fame. Early in the film, Elvis (Austin Butler) comes out before a dubious, lightly mocking crowd at the Louisiana Hayride in a pink western style suit and black lace shirt, either of which would have more than raised eyebrows in the period. Before he can launch into his song, a man in the audience yells out “Get a haircut, buttercup!” But as soon as Elvis wails the first note of “Baby Let’s Play House,” Luhrmann’s maximalist tendencies shift into overdrive and Elvis becomes a figure akin to a giant pink vibrator onstage, shimmying and shaking to the sounds of electric guitar feedback and bringing a significant portion of the women in the onscreen audience to apparent orgasm as the men in the crowd get increasingly agitated and angry. The costume here isn’t just historically accurate, it’s thematically appropriate as well. Elvis was known for wearing pink at a time when mainstream male pop and movie stars would not be encouraged to do so. His love of his 1954 Fleetwood Series 60 custom-painted pink (technically, the color was called “Elvis Rose”) Cadillac became so well known that it forced car manufacturers in the 1950s to start offering their cars in various shades of pink finishes. Elvis was a major social disruptor who took his musical style and his personal style from Black and sometimes queer musicians and performers like Little Richard, who showed him the freedom and the power in owning his body as a form of artistic and sexual expression and not limiting himself to good white southern Christian male comportment. These appropriations allowed him to display a form of unbridled male sexuality and peacocking that mainstream white America had not seen before. Luhrmann packed all of that into this one scene, allowing Elvis’s bright pink suit to serve as a throbbing and gyrating visual representation of forbidden sex and unholy music, embodying a secret history of queer presentation and African-American musical traditions.

The Politics of Pink

In 1998, activist Michael Page created the bisexual flag, partially modeled on the gay pride rainbow flag, incorporating the usage of blue, pink and purple to represent bi identity. The following year, transgender activist and author Monica Helms created the Transgender Pride flag, utilizing blue, pink and white stripes. In the case of the bi flag, the pink was meant to represent same-sex attractions. In the trans flag, the pink stripes refer to female gender. Queerness and femaleness. After the pink triangle came the pink ribbons in support of breast cancer awareness. At the turn of the 21st century, pink took on decidedly more political connotations. In 2000, the Pink Pistols, the LGBTQ defense group in support of responsible gun ownership was formed. In 2002, Code Pink, an anti-war and social justice organization founded by women, was launched. And as we mentioned previously, the largest single political protest in the history of America came on January 21, 2017, at the first Women’s March, which adopted pink knitted caps with kitty ears as its symbol of pissed-off and politically engaged women. Queerness, violence, pacifism, sisterhood, feminism. Because of the connotations applied to it, pink has spent most of the last century representing the competing ideas of frivolous femininity and a threat to patriarchal norms. There is no other color so heavily laden with specific, often topical, social or political connotations.

The Monster: Dolores Umbridge, played by Imelda Staunton in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (Dir. David Yates, 2007)

The Costume: A pink mohair dress with a matching cropped jacket with pink velvet buttons, trimmed in pink yarn fringe, fuchsia low-heeled Mary Janes, a kitten cameo brooch, a kitten cameo ring, designed by Janey Termime

The Quote: “You know, I really hate children.”

Pin

Pin

For this entry, we could have chosen any of a number of pink tweed or boucle suits or dresses, since it’s the only color she wears. Every piece is extremely conservative in tone, usually worn with a cat brooch or adorned with bows and ruffles, always with helmet hair in the Queen Elizabeth/Margaret Thatcher mode. While Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling explicitly denied a connection to any famous women like the Queen, Imelda Staunton said she took her inspiration from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who largely defined how female politicians dressed – conservatively, with coiffed helmet hair and traditional dress styles – for a generation, using a highly refined and curated persona as cover for political gamesmanship. She serves as an exemplar of traditional, conservative women who seek power, using retrograde femininity signifiers to mask their own authoritarianism and ambition. Dolores Umbridge is entirely composed of the most preciously twee, retrograde, traditionally feminine tropes, motifs and embellishments, from her kitten collective plates to her pink cardigans to her teacups and even her girlish little giggle. It’s clear that she loves this aesthetic, just as it’s clear that she knows how to utilize it to cover her racism and fascistic tendencies when she needed to; a practiced, curated frivolousness meant to render her harmless in the eyes of her enemies. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix costume designer Janey Termime has explained that the pinks Dolores wears throughout the film start off soft and pale but get increasingly saturated and vivid as her power and hysteria increase. Pink is, therefore, an indicator of her power and emotional state, directly tied to both.

In almost all of these cinematic instances, pink becomes partially the point of the character, even as its original connotations are subverted. Pink is still associated with the feminine, but in the 21st century, it’s rarely about softness or frivolity or romance. Instead, it becomes a rejection of those ideas. Like Dolores Umbridge’s kitten plates, Marie Antoinette’s ever-present pink cakes, Elvis’s Cadillacs, the Burn Book, and practically every item Elle Woods owns, pink becomes a totemic color that appears over and over again in the surroundings of a powerful woman or challenging man who wears it. Pink, in this way, isn’t a color or a style choice, it’s literally a way of life; a distinctly anti-patriarchal approach to the world with disruptive, queer, potentially violent, society-destroying undertones to it. Enter Barbie (slight spoilers ahead):

Pin

Pin

With Barbie, all of the society-threatening, anti-patriarchal undertones and allusions of pink in cinema went from subtext to loud-and-clear text. Barbie Land is presented as an entirely anti-patriarchal society, not as a threat to the order, but as a wish brought to life by all of the pink-wearers in the real world (women and queer people) who would benefit from seeing that order completely ignored.

Pin

Pin

When Barbie reaches the real world, she immediately changes her outfit for something she feels will help her fit in better. This is the outfit. Pink is utterly a way of life for her, as ever-present and as much a part of her as her own face. She does wear a few non-pink ensembles in the film. Barbie the doll was never an exclusively pink girl, after all. In fact, her fierce loyalty to the color only became a ubiquitous aspect of her branding in the nineties. But in Gerwig’s Barbie, pink is very clearly the most important, most present, most meaning-laden color in Barbie’s world. In some ways, this stolen cowgirl outfit must have felt like a comfort to her in such strange surroundings.

Pin

Pin

Kens in Barbie Land are essentially living a version of how the real world tends to treat women and queer people, as people who exist in the margins, expected to uphold and be happy with an order that was designed to prevent them from having any power or identity of their own.

Pin

Pin

It’s extremely notable and obvious how his entire look changes once he sees a world where men dominate and comes back to Barbie Land to “do a patriarchy.” His costumes are no less ridiculous – in fact, they’re significantly more ridiculous – but pink has been completely banished from the Kendom because it’s a color that has significant power to challenge the patriarchy.

Pin

Pin

Gerwig and the film’s brilliant costume designer Jacqueline Durran took all of those decades of cinematic subtext and made the militant, order-threatening connotations of pink the entire point of Barbie. The Barbies (and beta male Allan) all switch into these uniform jumpsuits in order to literally bring down the patriarchy that has infected Barbie Land. Pink reaches its cinematic apotheosis as an anti-patriarchal hue. It’s now the color of guerilla fighters and revolutionaries.

Pin

Pin

It’s notable that Greta Gerwig chose to dress in solidarity with her cast on the day that scene was filmed. Even if no one was walking around that set intoning that pink represents a threat to the patriarchal order, the very idea of it is so self-evident in the film that it really doesn’t need to be articulated at all. There have been so many threatening women and occasional men in pink in the history of the movies that its association with the destruction of society is nearly as strong as its association with femininity. Those pink pussy hats resonated for a reason. The brilliance of Gerwig’s film is that she understands Barbie as both a cultural figure and a political one. It’s not remotely a coincidence – or even surprising – that the film has become yet another lightning rod in the culture wars, with a whole phalanx of angry little men clenching their fists in response to it. And while we don’t think we’re necessarily the guys who should be exploring this point, we also don’t think there’s much of a mystery as to why Barbiecore and the entire fashion response to Barbie the movie became such a powerful and pervasive trend at exactly the same time women’s reproductive rights, trans rights, and LGBTQ+ rights have been delivered devastating blows. Pink has become the color of female and queer rage.

[Picture credit: Warner Brothers, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Universal, Columbia Pictures, Sony Pictures, Lionsgate, Focus Features, Pathé]

International Fashion Spotlight: Ghanaian Label Duaba Serwa Next Post:

The Star-Studded SAG-AFTRA ‘Rock the City for a Fair Contract’ Rally in Times Square

-

Pin

Pin

Christmas Movie Dress Advent Calendar Day 24: Vera Ellen in WHITE CHRISTMAS

-

Pin

Pin

Pop Style Opinionfest: T Lo’s Year-End Faves

-

Pin

Pin

Christmas Movie Dress Advent Calendar Day 23: Judy Garland in MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS

Please review our Community Guidelines before posting a comment. Thank you!