On June 28th, 1969, when the police entered the Stonewall Inn in the West Village for the sole purpose of harassing the queer people gathered there, a butch lesbian was reported to have gotten into a scuffle with the officers, possibly even having gone so far as to punch one of them. As they attempted to subdue her and get her inside the back of the paddy wagon, she was said to have turned to the watching crowd of queer folks on the verge of revolution and pleaded with them by uttering the immortal line, “Why don’t you guys do something?” After that, all gay hell broke loose.

Or so the story goes.

The thing you have to remember about Stonewall – and any other queer history pre-dating it – is that the people who were participating were literally outlaws and outcasts, disenfranchised and often racked with shame; existing and congregating in the underground and away spaces of the world. The Stonewall Riots weren’t just an event that received virtually no coverage in the media at the time, they were an event that wasn’t considered important until years after the fact, when the ensuing rise of the gay rights movement occurred in response to it. A flashpoint moment like Stonewall – a moment that no one saw coming, no one paid attention to, and even the people involved in it weren’t  likely to document – means it’s a part of recent history that’s as much myth and legend as it is fact and history. And no figure looms quite so large in the myths and legends of Stonewall as Stormé DeLarverie, the woman who went down in history – and legend – as that butch lesbian who punched a cop and lit a fire under the collective asses of the LGBTQ community. She has been called the Rosa Parks of the LGBTQ rights movement.

likely to document – means it’s a part of recent history that’s as much myth and legend as it is fact and history. And no figure looms quite so large in the myths and legends of Stonewall as Stormé DeLarverie, the woman who went down in history – and legend – as that butch lesbian who punched a cop and lit a fire under the collective asses of the LGBTQ community. She has been called the Rosa Parks of the LGBTQ rights movement.

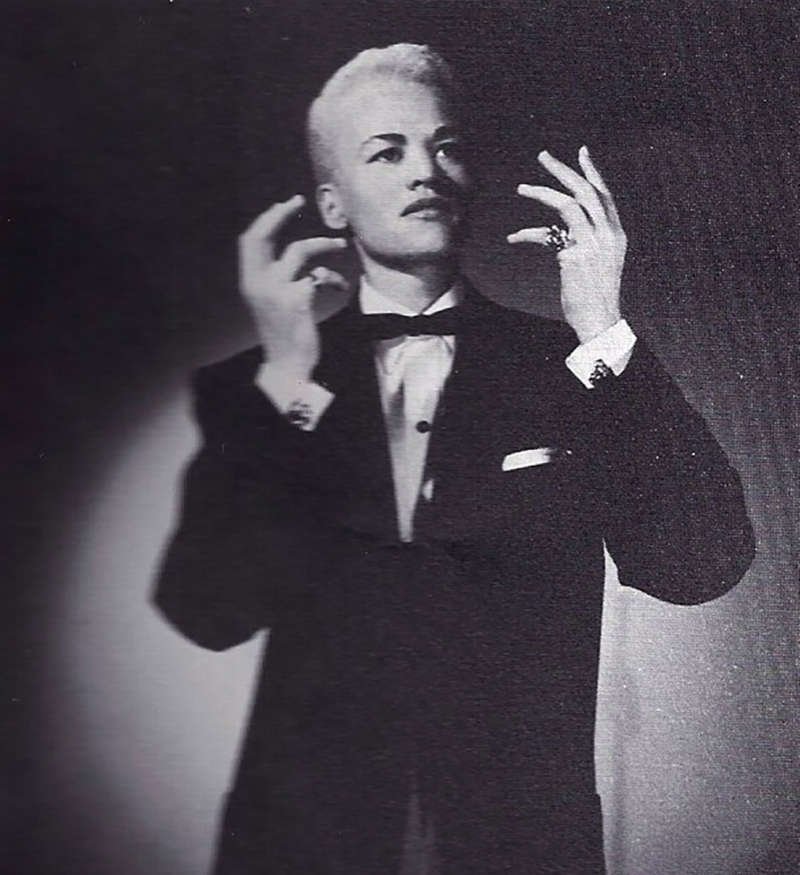

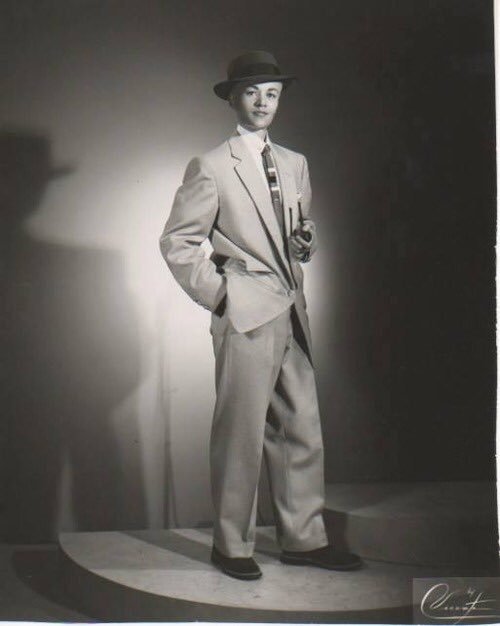

Born in New Orleans in 1920 to a black mother and a wealthy white father, Stormé gained a unique understanding of the world fairly early in her life as a butch queer woman of color who could reasonably pass herself off as someone at the opposite end of the privilege scale: a straight-presenting white man. In fact, when she dressed femme, she was often picked up by the cops for public transvestism (which was illegal at the time) because they assumed she was a man in drag. Performing was in her blood early and after a brief stint riding horses for the circus, Stormé found work as a singer and eventually landed a long-running gig with the legendary Jewel Box Revue. With a tagline of “25 Men and One Girl,” the Jewel Box was a mid-20th Century drag revue that traveled the country, offering the very best in gender non-conforming entertainment to mostly mainstream audiences who were perfectly fine paying good money to get a little queer glamour in their lives for one night. The 25 men of the marquee line were drag queens and chorus boys, but that One Girl, for well over a decade, was Stormé. With a debonair bearing and possessed of a smooth baritone, dressed in fine men’s suiting or formalwear, Stormé cut quite the chic and masculine figure as the only drag king many of the Jewel Box audience members had ever or would ever see. In fact, we would argue her time serving chic genderqueer realness to Middle America was as important in its own way as her mythical appearance at the riots and the work she did in the years following them. Drag performers were always some of the first visibly queer people most straight folks ever encountered and while it’s not likely many audience members left the Jewel Box Revue firm in their belief in the full humanity and equality of the people who just entertained them, it’s not a small thing for the deeply disenfranchised to offer to a hostile world an image of themselves that elevates their charisma, uniqueness, nerve and talent.

Immediately following the riots – which Stormé insisted on calling a rebellion rather than riots – her longtime partner died and she turned toward the newly energized and rapidly changing queer community to lose herself in her grief and to focus her considerable energy toward protecting them. For decades, the tough-as-nails former drag king worked as a bouncer for a succession of West Village lesbian bars and when she wasn’t on the job keeping her sisters safe, she was patrolling the streets of the neighborhood, constantly on the lookout for any queer family members who might be in trouble and might need a hardass butch to step in and offer her now-legendary fists to help them out. She was active in the advocacy and organizing end of the community as well, serving for many years on the board of the Stonewall Veterans Association and eventually becoming its Vice President. She died at the age of 93 in 2014, in the care of the community she had spent her life caring for herself.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter if Stormé punched a cop at Stonewall. It doesn’t matter if anyone did. What matters is what we know happened and then what we know happened afterwards. Queer people rose up in the face of social genocide and from that rising up discovered a sense of identity and purpose for themselves. It’s okay for us to have myths and legends. No one wanted to record our history so we’re allowed to make up one that pleases us or raises us up. Stormé DeLarverie was a legendary entertainer, a smoothly charismatic figure, a firebrand, a rebel, a sister, a father figure, a fighter and a protector. As she says best in her own words, she was “a survivor who helped other people survive.” THAT is why she’s a legend. She was the very best of us.

“Our book Legendary Children: The First Decade of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Last Century of Queer Life is on sale now!

The Los Angeles Times called it “a nuanced exploration of the gender-bending figures, insider lingo and significant milestones in queer history to which the show owes its existence.” The Washington Post said it “arrives at just the right time … because the world needs authenticity in its stories. Fitzgerald and Marquez deliver that, giving readers an insight into the important but overlooked people who made our current moment possible.” Paper Magazine said to “think of it as the queer education you didn’t get in public school” and The Associated Press said it was “delightful and important” and “a history well told, one that is approachable and enjoyable for all.”

Laura Linney, Elliott Page, and Zosia Mamet at “Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City” New York City Premiere Next Post:

Henry Golding in Tom Ford at the 2019 Fragrance Foundation Awards

Please review our Community Guidelines before posting a comment. Thank you!