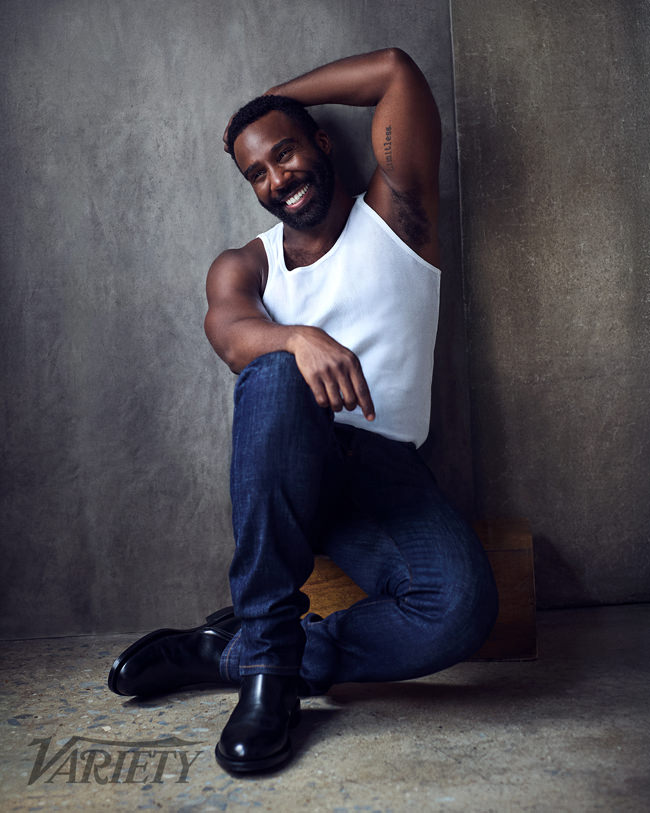

In a new cover story for VARIETY, SEVERANCE breakout Tramell Tillman speaks with Chief Awards Editor Clayton Davis about his historic Emmy nomination as the first openly gay Black man to be recognized in the supporting actor drama category. He also talks about working with Tom Cruise on MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE — THE FINAL RECKONING, SEVERANCE theories about his character Milchick, bringing HBCU culture to the iconic drum scene in Season 2, his coming out story, and more.

Tillman on learning about his Emmy nomination: “I was shaking all morning, and I kept telling myself, ‘I just want it to be over. I want 11:30 to come and go so I can just know and move on with my life.’ I kept telling myself, ‘Tramell, no matter what happens, it’s OK. It’s all right. It’s not the end of the world.’…My manager had set up a Zoom link for the team — if it went our way, everyone could hop on and celebrate, and if it didn’t, there was no pressure. So when the list came out, my manager says, ‘Outstanding supporting actor in a drama series: Tramell Tillman from “Severance!”’ and I was jumping up and down. That’s when my team revealed their screens, and they all had ‘Tram-Emmy’ shirts on.”

On whether he feels the pressure of potentially historic win: “Do I feel a weight? No. I feel honored to join the legacy of these incredible storytellers. I’m ambitious and would love an Emmy, but I’ve learned it’s not up to me.”

On working with Tom Cruise on “Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning”: “On my first day, I filmed the doughnut-garage scene. I had gotten the script only the day before, and I was shaking in my boots. I was taken by his strength, grace, humility and passion. Definitely passion.”

On theories that Milchick is a prisoner as well: “I can understand that theory. It’s hard for me to answer because there are so many questions that I have about the character myself. What scares me is his potential. How he moves his eyes, how he moves his head. Everything is methodical.”

On bringing his HBCU experiences to the drum scene in Season 2: “When I learned there’d be a celebration with a band, I didn’t want to reinforce a stereotype of ‘Every season the Black man dances.’ They understood. I wanted Milchick’s movements to feel intentional, not random; this wasn’t a co-worker who just showed up to kickline for no reason — it followed his being policed over vocabulary, terrible paintings and boardroom disrespect. Yes, it celebrates Mark, but this is also a moment for Milchick: Just like Tramell needed to be seen, Milchick needed to be seen. It was very important for me that this character did not shy away from his Blackness. I asked if we could infuse HBCU energy — that’s how we got that style. That celebration was for him. That was him reclaiming joy. I knew it would feel authentic.”

On the long hiatus between seasons and what caused the delays: “I was a little nervous if the fans were going to come back. There’s no telling, and there’s so much quality programming out there. But I knew that we had to finish. I knew that there was too much invested in this show for it not to finish. It was just a matter of when and whether the fans would stay with us. I’m grateful that they did…The delay was outside of our hands. The first season, it was a pandemic. Second, we had two strikes. We’re a show that doesn’t rush. We want to take our time. This show needs that. I think the more we do it, we find our groove. We know who these characters are to a certain extent. We know how they move.”

On his coming out story: When Tillman was in his 20s, he turned to his mom and said a truth that has matured quietly inside him for years. “Mom, I’m bisexual,” he says to her, his eyes fixed on the road.

“Well, how’s that going for you?,” she replied. Tillman laughs softly at the memory now. No dramatic climax or emotional hug followed, he says. Just the acceptance of a deeply religious woman who was, and still is, the closest to him in the Tillman family.

Some years later, a second conversation follows, more direct this time, with no ambiguity: “I’m gay.”

This time, her response lands with different gravity, not laced with judgment, but with fear. “I don’t want this to ruin your career,” she told him. “I don’t want you to be blackballed. I don’t want you to be pigeonholed.” This isn’t disapproval; it’s preparation and protection from a mother who knows how the world punishes those who dare to live truthfully — especially a Black man.

“Anyone you bring home, I will embrace him as my son,” she then said.

On being the first Black man to finish the University of Tennessee’s MFA program: “The head of acting warned it might be a deal breaker — I’d be the only Black person in that program, and nearly the only Black male among faculty, staff and students. I thought, ‘Hey, free education; I’ll learn.’ But I didn’t grasp what I was signing up for until I moved there. It was never intimidating — more frustrating, over- whelming and isolating. I endured being called the N-word, followed and taunted with ‘White power!’ There were countless microaggressions. When I reported incidents, some in the community would say, ‘Well, I didn’t see it,’ or ‘I didn’t think it was racist.’”

On his religious upbringing: Sundays looked like the “First Baptist Church of Highland Park. Every Sunday, we were in church and dressed for church. We weren’t allowed in the living room — that was for fancy moments. We had this beautiful crushed-velvet blue couch with gold accents. Music always played in our household, but on Sundays, church music. So we would go from Temptations, Aretha Franklin, Tupac, Biggie, Janet on weekdays to Sunday morning: Shirley Caesar, Kirk Franklin, Mississippi Mass Choir. That was our way of making sure that we kept the Sabbath holy.”

However, his mother and father had different views on faith.

“My mom used church as a coping mechanism, but my dad rejected it. He’d say, ‘I’m not anti- white; I’m pro-Black, and I don’t see why I need to worship a white Jesus.’ He hated hymns that talked about being ‘washed white as snow.’ There was this stark dichotomy when it came to faith in the home, because my mom really believed in the teachings of Jesus Christ, and my father believed more in community and self-reliance. He stopped going to church with us. When we would go to early-morning service, he would say, ‘Oh, y’all going to get God out the way early.’ Even as a kid, something about that made me bristle.

I felt that God and the art saved my life. I’m a person who still prays and believes.”

On not feeling seen for who he truly was as a child: “There were moments that I felt release or freedom through the art form, because I could get away from the negativity. For me, acting was a vessel to escape, to avoid, to run away. Dancing was a way for me to allow my body to be free and express itself. Singing was a way to be heard in a different way, to allow myself to be loud. A lot of my childhood was about survival. I had to learn how to survive, produce and be excellent. I think with all those pressures, there weren’t moments where I felt seen, because I didn’t know who I was. I was hiding behind singing, acting, dancing, writing, performing. I’m always a little jealous when people talk about their first crush or first kiss — I don’t remember those.”

On his dream project: “I’d adapt African folktales and fairy tales, cast- ing Colman Domingo, Mahershala Ali, Lupita Nyong’o, Sterling K. Brown, Jeffrey Wright, David Oyelowo, Michael B. Jordan and Nicole Beharie.”

[Photo Credit: Richard Phibbs for Variety Magazine – Video Credit: Variety/YouTube]

CAUGHT STEALING Star Austin Butler on THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON Next Post:

Red Carpet Rundown: WEDNESDAY ‘Doom Tour’ Press Conference in Sydney, Australia

Please review our Community Guidelines before posting a comment. Thank you!