After last week’s Brooklyn post, we should have probably made it clear that it’s part of a planned trilogy of film costume posts centering around mid-20th Century women, with each film representing not only a different kind of woman, but a different approach to costume design. And with each post, we hope to sort of stretch our muscles a little and examine each film differently.

The costumes of Brooklyn repeated themselves in order to ask the same questions the character was being asked. Each costume represented the main character’s central choices, in a film that was largely about the choices one makes for the direction of their life. With Carol, we’re more interested in the way the costume design (by the amazing Sandy Powell) defines the central relationship between the two main characters; the way it lightly touches on the worlds each comes from and then mashes them together to force juxtapositions and lay bare the emotional core of the relationship between Carol Aird and Therese Belivet. It’s not about using costume to define or embellish story points and narrative themes, as with Brooklyn; it’s about costumes designed to explain who the two main characters are, how they see each other, and why they fell in love with each other.

Whew! That sounds heady and serious. But ironically, this sort of character-based read tends to express itself in the simplest of motifs. In fact, we’re going to lay them out ahead of time for you, like the chapter titles of a book. Here are the themes to look for while watching Carol and paying attention to the costumes: The Loud Boy, Sapphic Suiting, The Hands of a Lady, The Looming Silhouette, Hat vs. Hat, The Mentor and the Schoolgirl, and finally, Suit to Suit.

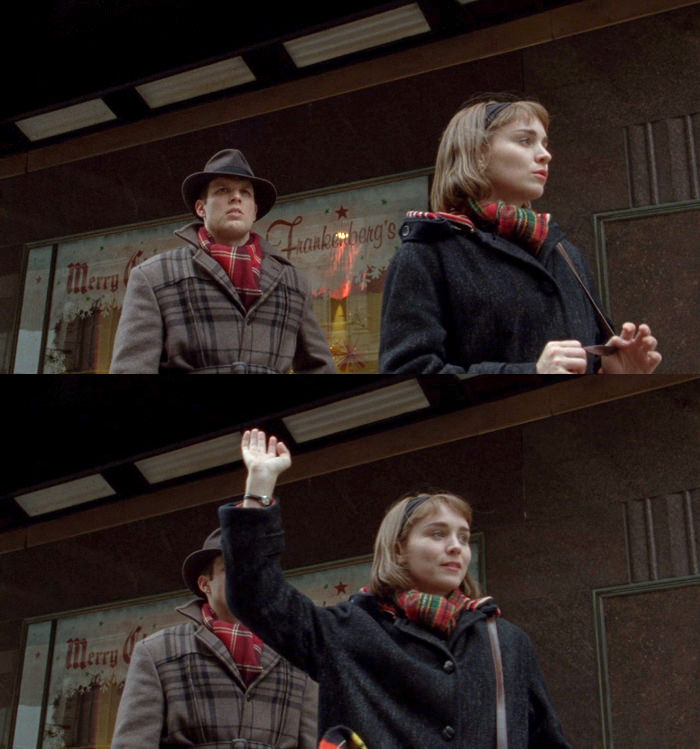

1. The Loud Boy

Therese’s ostensible boyfriend Richard offers a large, domineering silhouette in his scenes with her. This is not the only time the film will use Rooney Mara’s small size to pay off certain costume design choices to make her appear overwhelmed by someone.

Richard’s shape is distinctly masculine, with exaggerated shoulders paired with a tightly defined waist, fedora, and a high collar. While he’s mostly presented as jovial, clueless and entitled, his presence always buzzes with an underlying threat or sense that things could turn dark on a dime. This is helped along by the clashing plaids of his outfit and the way Therese’s own clash of stripes and plaids speak of her mindset when she’s around him: overwhelmed, confused and discordant. Like all her male drinking buddies, Richard is merely something loud and domineering to distract her from, as she later puts it, becoming “more interested in humans.”

When he strips away the jovial facade and nice-guy approach to accuse her of having a crush on Carol, it’s interesting to note the sudden change in his costume. We always see these two outside, wearing their clashing coats and scarves. Here, he continues to present as a visual annoyance, distinctly masculine in shape. What’s interesting is how his sweater perfectly mimics the one Therese was wearing when she met Carol, a visual callback to what he sees at that moment as the source of his problems, as well as a character motif that places him as another person obsessed with Carol and what she means.

This is the world Therese inhabits when she meets Carol. A hyper-feminized, hyper-infantilized world of pink and babydolls that leaves her distinctly uncomfortable in her department store job, and a world of loud, distracting, jovial but entitled men she keeps at arm’s length in her social and romantic life. Given the way she interacts with the few female characters in the movie other than Carol (her boss at the department store, Carol’s friend Abby, the girl at the party who hits on her), it would seem that women tend to make her somewhat uncomfortable. This is of a piece with how she tends to initially see Carol as an intimidating figure.

Now let’s shift over to the world Carol inhabits. It’s chic, lightly androgynous, and tailored to within an inch of its life.

2. Sapphic Suiting

Carol’s preference for tailored suiting with lightly masculine details serves two purposes. First, it places her as a stylish and well-to-do woman of the time. While her suits aren’t youthful in tone, they are nonetheless very chic and clearly of high quality. And we should note that, because the details and styles of these suits were au courant and popular for the time, they would not have read as androgynous or gender non-conforming in any way.

However, in the context of a modern film they work as a way to set her apart from other women (note the wife of her husband’s colleague at the party and the vast difference in their styles) while at the same time tying her visually to open lesbian characters, such as her friend Abby or the two women who cruise Therese in the record store. We would argue that both Abby and the women in the record store were coded (and would have read to the initiated as) lesbians at the time by the way they’re dressed. Carol is flying under the radar, so to speak, so her fitted, skirted suits with more delicate details only lightly call to her out-and-proud sisters.

In addition, we should note how fitted and womanly her silhouette tends to be, whether she’s in a suit or the many times she wears dresses. Carol is presented as a sometimes extreme form of mature femininity through Therese’s eyes, so her fitted and shape-conscious dresses and suits are somewhat buttoned form of sexiness.

Carol’s heavily coded and slightly fetishized femininity as well as the importance of her silhouette are best exemplified in the next two motifs, which underline how Therese sees her.

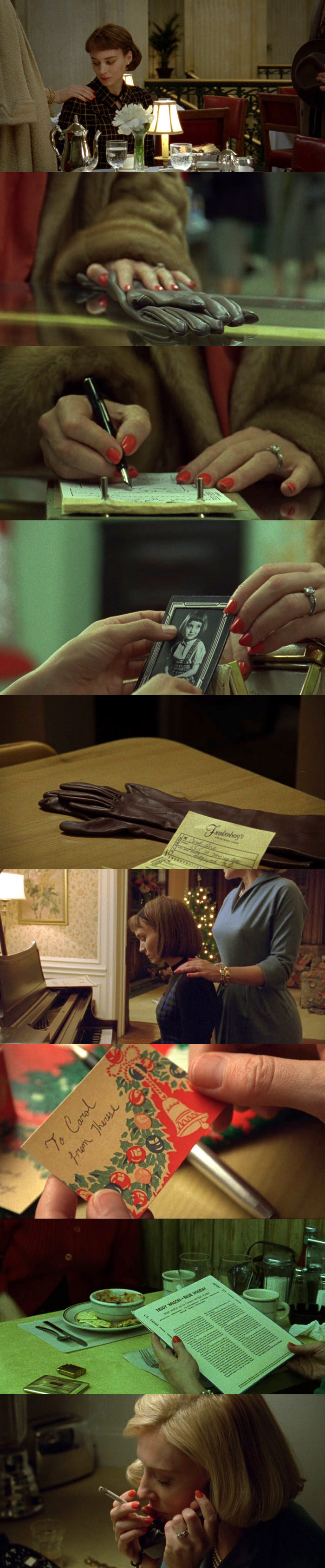

3. The Hands of a Lady

Carol’s laquered pink nails are as much a character-defining part of her visual as her fur coat or body-skimming suits. The color speaks of traditional femininity, of course, while the relentless perfection of her manicure speaks of a life of comfort, in which a lady’s hands are never anything but perfectly presented. These hands are telling the world that they never scrub toilets or pin clothes to a line, and they certainly have never pinched a penny.

Both the viewer and Therese herself are introduced to Carol’s hands first. Her hands are often framed in mid or extreme closeup throughout the film. It’s not a coincidence that Cate Blanchett does some considerable hand-acting with Carol. This character would certainly have presented and composed herself in the most ladylike of manners, and at the time, that would have included presenting your hands in specific ways and poses. This is how a lady holds a cigarette; offers a picture, signs her name.

Also, putting Carol’s hands in so many extreme closeups constantly highlights her married status (the source of all her pain and the thing that will later tear Carol and Therese apart) as indicated by her ever-present engagement ring and wedding band. In addition, she consistently wears somewhat showy or noisy bracelets, which tend to underline her wealth. The few times we see Therese’s hands in the film, they are framed to highlight her own unvarnished, un-manicured nails, in order to draw a difference between the two women, something practically all of their costume elements do. Carol is ladylike, well-to-do, and composed of socially acceptable artifice; Therese is girlish, youthfully unformed, and unpretentious. All that character information, just from hands.

But defining Carol as a ladylike, married, well-off, traditionally feminine figure isn’t the only reason her hands are presented so often. In several instances, Carol’s disembodied hands are shown to creep into the frame, touching Therese. This is of a piece with how Therese sees Carol; how most inexperienced people see the objects of their infatuation: with a mixture of romanticism and fear. Carol unsettles Therese considerably, which is why she will be occasionally framed in a disembodied, slightly Hitchcock style, like one would shoot someone about to commit a murder. It’s also why Carol’s gloves become something of a totem or fetish for Therese; an item of extreme focus and importance, although she couldn’t quite say why.

This method of underlining Carol as a slightly frightening figure to Therese is also embodied by the way her silhouette changes during the story.

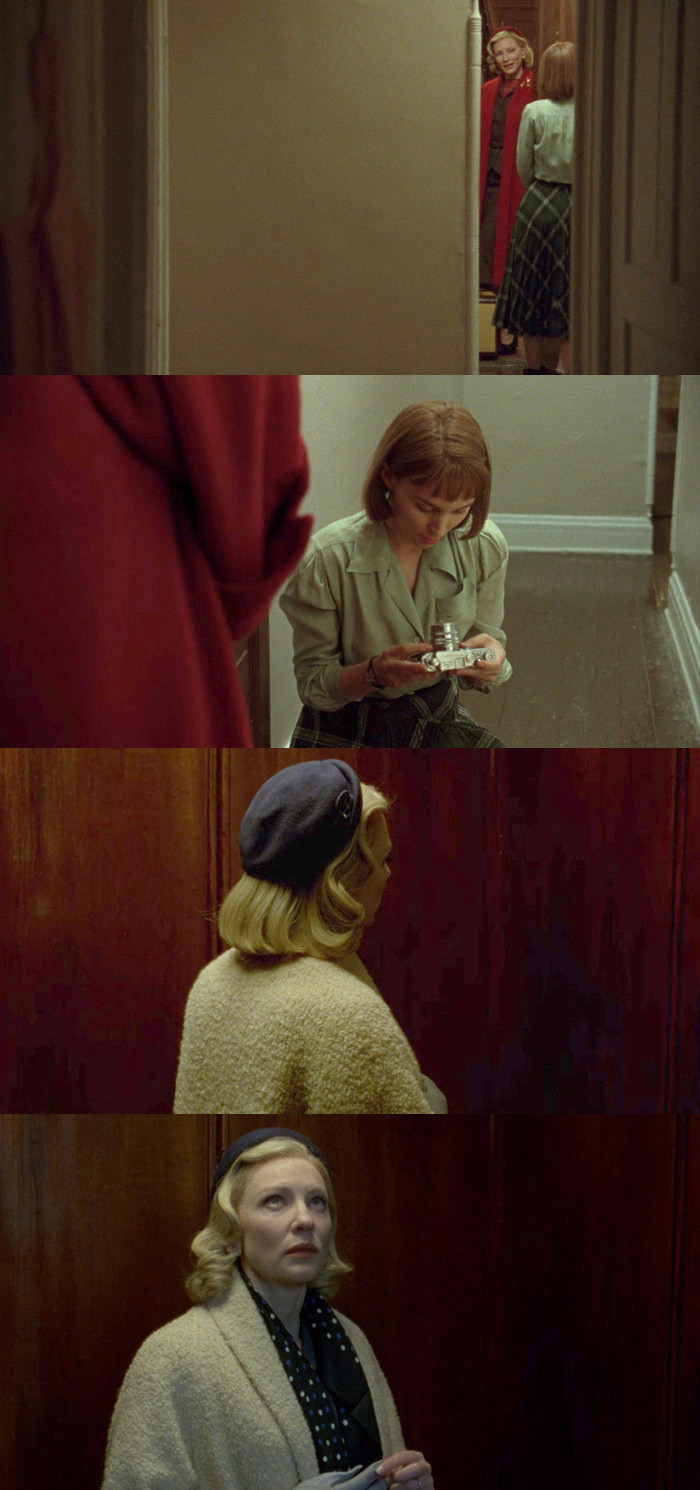

2. The Looming Silhouette

Despite Carol’s delicate ladylike nature and style, the film often portrays as her as a massive figure. Part of this plays into the natural size differences between Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara, but it’s helped along by some coat designs that give her character a larger, fill-the-frame kind of visual footprint. This fur coat in particular does double duty; helping to portray Carol as a large, vaguely predatory creature (from Therese’s perspective), but also serving as a demonstration of how Carol’s wealth and status are weighing her down.

This silhouette appears whether Therese is in the scene or not, although her appearance or lack of it tends to alter the feeling of these large silhouettes (which we should note were very much in style for the time). When Carol is on her own, dealing with the threats to her status, lifestyle and motherhood, these oversized coats have a swaddling, blanket-like effect, while at the same time situating her as a large outline on the screen.

In this way, Carol’s oversized coats reveal both her fears and vulnerability (coat as armor, coat as swaddling) when she’s alone. When she’s with Therese, they help underline the younger woman’s feelings, which are a heady mixture of fear, infatuation and lust at this emotionally large and potentially overpowering figure. Again, costume as character, costume as embodiments of emotional states.

And now a few (and only a few) words on hats.

5. Hat vs. Hat

The film is mostly set at Christmastime in the northeastern part of the United States, so outerwear and hats played a big part in the costuming simply for time and place reasons. But like all the other elements of the costume design, the hats tell the tale of each character, whether we’re watching Therese in a Santa hat becoming instantly infatuated with Carol in her demure, ladylike fascinator-style cap (one in a series and range of colors), Carol and Abby assert their sisterhood with distinctly colored scarves, or Therese play the schoolgirl or the go-along-to-get-along gal in her colorful tam. It’s that latter style, and how it plays against Carol’s more demure and refined hats, that makes a good launching point to illustrate the most dominant and important costume theme in the whole film.

6. The Mentor and The Schoolgirl

Without the story openly referencing it very often, the costume design of the film rather firmly illustrates and underlines both the age differences and the status differences between the two main characters. In early scenes of their interaction, this is almost comically overt, such as their meeting in a toy department, with Carol oozing wealth and maturity in her clothes, while Therese wears a silly hat (over a distinctly girlish headband), demure sweater and schoolgirl-style jumper.

This overt form of costume differentiating continues into their first “date:”

Older, suited woman dripping with status and traditional femininity, and younger, unpretentious-to-the-point-of-plain girl in a headband, blouse and jumper. “A strange girl,” Carol calls her. “Flung out of space.”

Older, suited woman dripping with status and traditional femininity, and younger, unpretentious-to-the-point-of-plain girl in a headband, blouse and jumper. “A strange girl,” Carol calls her. “Flung out of space.”

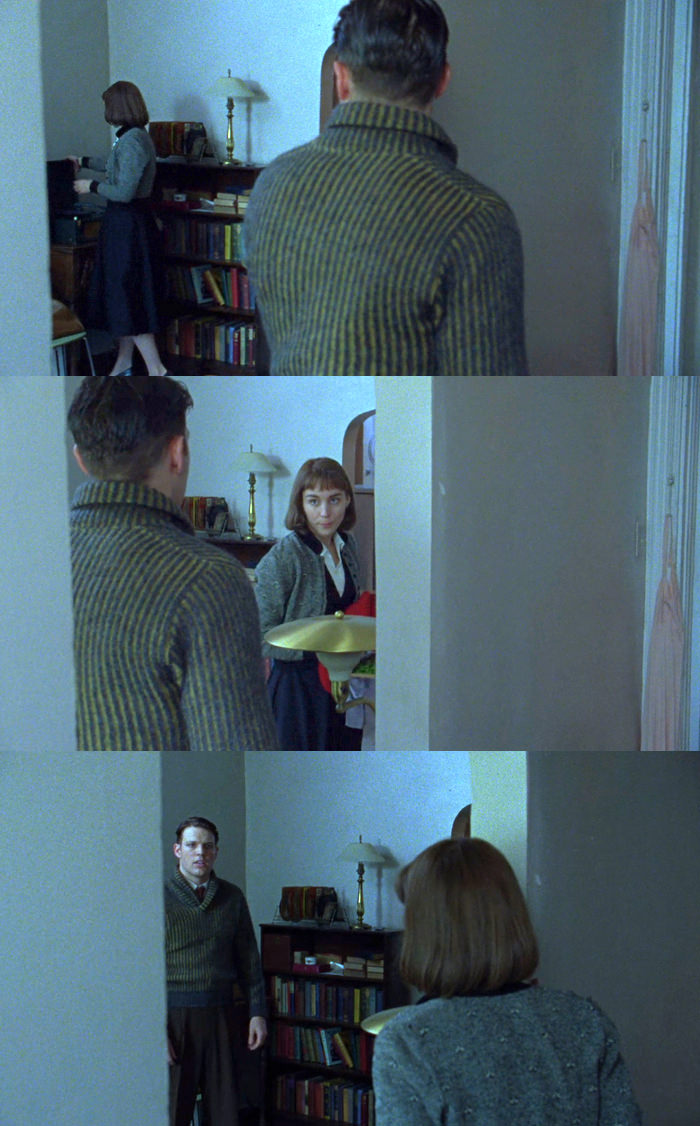

The theme continues again the first (and only) time Therese visits Carol at her home:

Note how Carol is in a body skimming dress and barefoot in her own home, giving the scene a more openly sexual vibe than their previous scenes, while Therese remains almost comically girlish and innocent in tone.

It’s a theme that continues lightly throughout the film, sometimes more overtly than other times:

Just a clear and consistent sense that one woman is mature, sexual and sophisticated and she’s teaching the other one, who is young, fresh and wide-eyed; a point referenced more than once in the dialogue. “I want to ask you things,” Therese says.

Things to note in the above collages: the way the vertical lines of T’s sweater and C’s fur coat speak of a connection when they meet; the sexy dresses C wears on their road trip, as well as the padded shoulders and plaid of her bathrobe, which gives her an almost paternalistic vibe, and the men’s style plaid blazer worn with pants.

And finally, the story reaches its natural end point, as the two former lovers meet up again, each heartbroken in different ways, each of them changed; one more obviously than the other. “I have much to do,” Carol wrote in her breakup note to Therese, “And you, my darling, even more.”

7 . Suit to Suit

No schoolgirls here.

Therese has matured because of her first love, first heartbreak, and the launch of her career at the New York Times. Carol remains Carol; feminine, suited, perfectly accessorized, but for the first time in the film, Therese is dressed up to her level and station. Note the sudden appearance of earrings on her, along with the shaped (and oh so Audrey Hepburn) brows, eye-catching neckline and the red bag, as well as the slightly more stylish and youthful silhouette, with its flared skirt. For the first time, Therese’s look speaks of success and refinement, but also youth and energy. She is who she was, the person who captivated Carol, just older and more experienced; ready to be with her.

Woman to woman. Suit to suit.

[Photo Credit: Weinstein Co. – Stills: Tom and Lorenzo/Weinstein Co.]

Everyone’s Gagging Over This First Image of Renée Zellweger as Judy Garland, But We’re Not Feeling It Next Post:

“Howards End” Hits the Ground Running with a Lush Adaptation

Please review our Community Guidelines before posting a comment. Thank you!